How to Write at the Speed of Change

Are we overstimulated, yet underskilled?

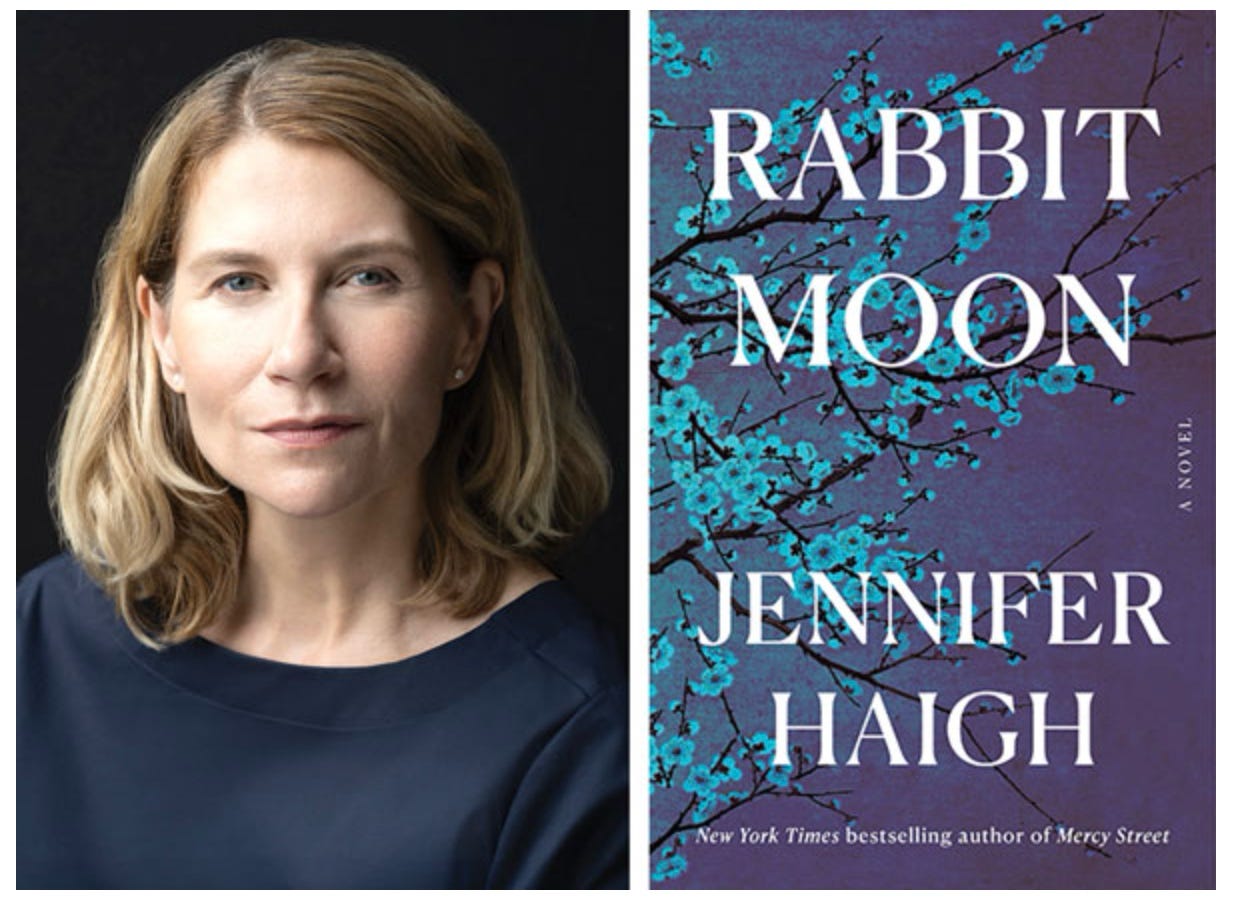

In last week’s pod interview with Jennifer Haigh about her new novel Rabbit Moon, Haigh discussed how everything in Shanghai, China–where the story takes place – “moves at an accelerated pace.” The rate of change in Shanghai, she says, was like nothing she’d ever experienced.

That’s to be expected for a city of 30 million people, many of whom are fairly young. It does pose an interesting dilemma for a novelist, and not necessarily an unwelcome one. After all, fiction writers happily set time constraints of all sorts for their characters: A day, a year, an era, even the length of a single blow job (thanks to Susan Minot, I’ll never forget that). They also happily compress time, jumping from one century to another or from the prehistoric age far into the future. (Of course, just because they do so happily doesn’t mean these shifts are easy; let’s remember that it isn’t always simple to remember how time was spent, let alone measured, in a different era.)

What interested me about Haigh’s statements, that is to say what my mind snagged on, is the idea that change is happening faster than ever before, especially in places like Shanghai. A couple of years ago my older daughter traveled for a few months in Asia. When she reached Seoul, Korea, she stayed for just a couple of days, saying that the city is so advanced and busy that she felt overstimulated by its daily culture. She moved on to Indonesia and relished its slower pace.

Not every writer, or any other creative, has to keep pace with modern methods. There will always be someone writing a long, linear story, someone crafting slow poetry, someone painting an exquisite leaf. But I wonder if we are best served, as writers and as writing instructors, by reading and assigning too many works of literature that neglect how politics, technology, ideas, and climate can affect the speed of human actions and events.

It’s one thing to read Moby Dick (a book I just confessed to never having read; don’t @ me) and emphasize how the whaling industry had to rely on wooden ships and sextants. It’s another to expect students to write with Melville’s cadences–or Welty’s, or even Anne Tyler’s. I wonder, without knowing enough about other writing programs, if we should be focusing on exercises and techniques to help emerging writers capture as much as they can if it serves them. One of the issues that has come up recently is about how badly prepared archivists are for all the online material coming their way. I hope we can help writers prepare to figure out which material is most important to their work, and how best to arrange it – in a timely manner, amirite?

Yours ever,

Bethanne

TUESDAY’S TOP 10

The new book releases that will open your mind and empty your wallet. . . As usual, in no particular order.

An Oral History of Atlantis: Stories by Ed Park — Sharp, funny short stories from the Pulitzer-finalist that encompass the last 25 years.

Fine Young People: A Novel by Anna Bruno — Mash up Rebecca Makkai’s I Have Some Questions for You and The Year of the Gadfly by Jennifer Miller; a student at a Jesuit high school investigates a classmate’s death.

The Winds from Further West: A Novel by Alexander McCall Smith — A new series from McCall Smith? Sign me up, as it involves the Isle of Mull, wolf cubs, and an opposites-attract romance between a veterinarian and a scholar.

Lonely Crowds: ANovel by Stephanie Wambugu — Ruth and Maria meet at a Catholic girls’ school and eventually accompany each other to early 1990s Manhattan, where their strong bonds will be tested by sex, art, and obsession.

The Conjuring of America: Mojos, Mermaids, Medicine, and 400 Years of Black Women’s Magic by Lindsey Stewart — An important contribution to American history, about the powers and oppression of Black “conjure women” over the centuries, whether gathering herbs, detecting water, or caring for community.

Sloppy: Or, Doing It All Wrong by Rax King — King, host of the “Low Culture Boil” podcast, writes a damn fine essay, whether it’s about a familial devotion to 12-step programs, shoplifting as pastime, or stripping to pay college bills.

The Man Who Died Seven Times: A Novel by Yasuhiko Nishizawa, trans. Jesse Kirkwood — The English-language debut of a great Japanese mystery novelist, in the vein of Richard Osman and Elle Cosimano.

The Good Liar: A Novel by Denise Mina — When a medical examiner discovers her evidence was wrong, she becomes tangled up in a high-profile court case.

The Dance and the Fire: A Novel by Daniel Saldana Paris, trans. NAME TKis

Terrible Virtue: A Novel by Ellen Feldman — Margaret Sanger founded Planned Parenthood and was a committed eugenicist. These things weren’t antithetical to her; Sanger, one of 13 children, was larger than life. Fascinating.

GET LIT:

Links that led me down the rabbit hole. . .

“A slave plantation was a lethal place not only because of the violence. . . but also because the sugar mills themselves were death traps.” – Mathelinda Nabugodi, The Trembling Hand: Reflections of a Black Woman in a Romantic Archive, excerpted on Lit Hub

A new George Saunders novel! Rejoice!